Can ‘cold-blooded’ advanced technology eliminate bias?

Advanced technology will lead to different types of forensic science review, says Robert Thompson, senior forensic science research manager at the National Institute of Standards and Technology. He says the objective findings, though, will only be complementary to expert testimony, and will not replace it.

The technology will add to the training, research and experience of examiners, he said, and could support or contradict their subjective opinion.

“This technology is independent of where it is going to be used,” Thompson said. “Adding the value of an objective measurement helps to maybe eliminate or control biases or anything like that, because it's cold-blooded, and it tells the examiner whether [they’re] making the right opinion or not.”

But Fabricant has his doubts. Just because technology advances doesn’t mean it pushes toward justice, he said.

“What we need is a scientific agency, something like his national institute, to do validation research and demonstrate that these techniques are reliable before they can be used in any criminal case,” Fabricant said.

This would allow independent verification of wild claims sometimes accepted as evidence in criminal trials, he said.

Thompson says people are interested in the objective measurements of technology, even though he believes subjective comparisons are accurate.

“Juries are getting wiser,” he said, “and they want to hear a little bit more about what’s the basis for the examiner’s opinion.”

Dror agrees with Thompson, as technology will provide that objective lens with juries. But, biases that people who create the technology have, or how people interpret the results, may impact the accuracy of their conclusions.

“The technology may be testifying [to the accuracy of the conclusion], but the human is talking,” he said.

DNA is nearly 100% accurate when a large sample is analyzed properly, says Becky Steffen, forensic DNA scientist at the National Institute of Standards and Technology. But such large samples are rarely the case.

A more sophisticated type of DNA testing, known as probabilistic genotyping now exists, enabling scientists to test mixtures that include DNA by different people.

Fabricant marvels at the advanced technology, but worries it could lead to wrongful convictions.

Expert testimony is normally paid for by the state at the request of the prosecution, and many of those experts are from the state Crime Lab. They are supposed to be “neutral, but they’re not because they work for the Department of Public Safety — the largest police organization in the state,” said Mississippi State Public Defender André de Gruy.

“The problem in most cases is the defense doesn't get anyone, and they're dependent upon the state expert to not only tell the truth, but to tell the whole truth,” de Gruy said. “If somebody's paying you and they're not asking you for the whole truth, you might not give the whole truth.”

Since the defense then cannot have the expert testimony reviewed by another scientist, it’s difficult to challenge their version of truth, de Gruy said.

Some defense lawyers don’t push for funding for experts because they’ve never received it in the past, de Gruy said. More than half the circuit judges in Mississippi are previous prosecutors.

“Judges would bristle at the idea that they’re on the same page as the prosecutor because by law they’re neutral,” he said, “but they don’t have the experience to understand why you need someone, even if it’s just a consulting expert, so that you can understand what the state’s experts are saying.”

Dror says that, while pathologists and examiners may be aware their conclusions could be subjective and subject to different biases, they don’t outright share that with the jury.

“The problem with being honest with the jurors is that they do not want to hear ambiguity,” Dror said. “They want to know definitely if the person is guilty or innocent. They want a clear conclusion and they want the scientists to take the burden off of them and give them a conclusive answer.”

Dror believes the legal system pushes scientists to not explain the complex nature of their conclusions, as they only care about an innocent or guilty verdict, not what happens in between.

With popular shows like CSI showcasing forensic science, juries may expect forensic evidence, and, when they see such evidence, combined with expert testimony of someone in a “white lab coat,” it can sway them, Dror says.

The CSI effect encourages this type of end-all, be-all mentality with juries, as an increased interest in true crime has led to an uptick in “couch detectives,” Steffen says. This distortion impacts a jury's ability to understand the intricacies of DNA and forensic evidence analysis, as crime TV makes the process look simple, fast and undeniable.

“There is so much technology out there that people are just demanding DNA. There’s no real evidence that that’s actually happening in court, but I think it helps strengthen a case,” she said. “Juries really like to see that if there's a match, then there's no arguing with it.”

The CSI effect is not the only aspect of forensic science that impacts juries, but a highly emotional case, where a baby is dead, causes desperation from police and prosecution to find the killer, said Dunham.

“They are much more likely to resort to questionable evidence, and juries are persuaded by it,” he said.

A 2014 study from the University of Denver investigated whether, as the seriousness of a crime increased, so would the use of erroneous evidence. Are crimes that have the highest stakes, like a death sentence, the ones that use the most unreliable evidence?

“If that’s true,” Phillips said, “then it suggests a problem with the death penalty that the worst crimes often attract the worst evidence.”

While it was found that the more serious crimes had a higher probability of different types of problematic evidence, such as false confessions, Phillips says it's hard to know if that translates correctly as the data sample only included known wrongful convictions.

“It's clear that as the crime gets worse, the chance of a false confession goes up. But we can't say for certain what's happening there,” Phillips said. “But what we think is happening is, [for example], the police aren't going to push as hard as they can for a stolen bicycle. But when there's a rape and murder and torture, the interrogation room probably looks really different.”

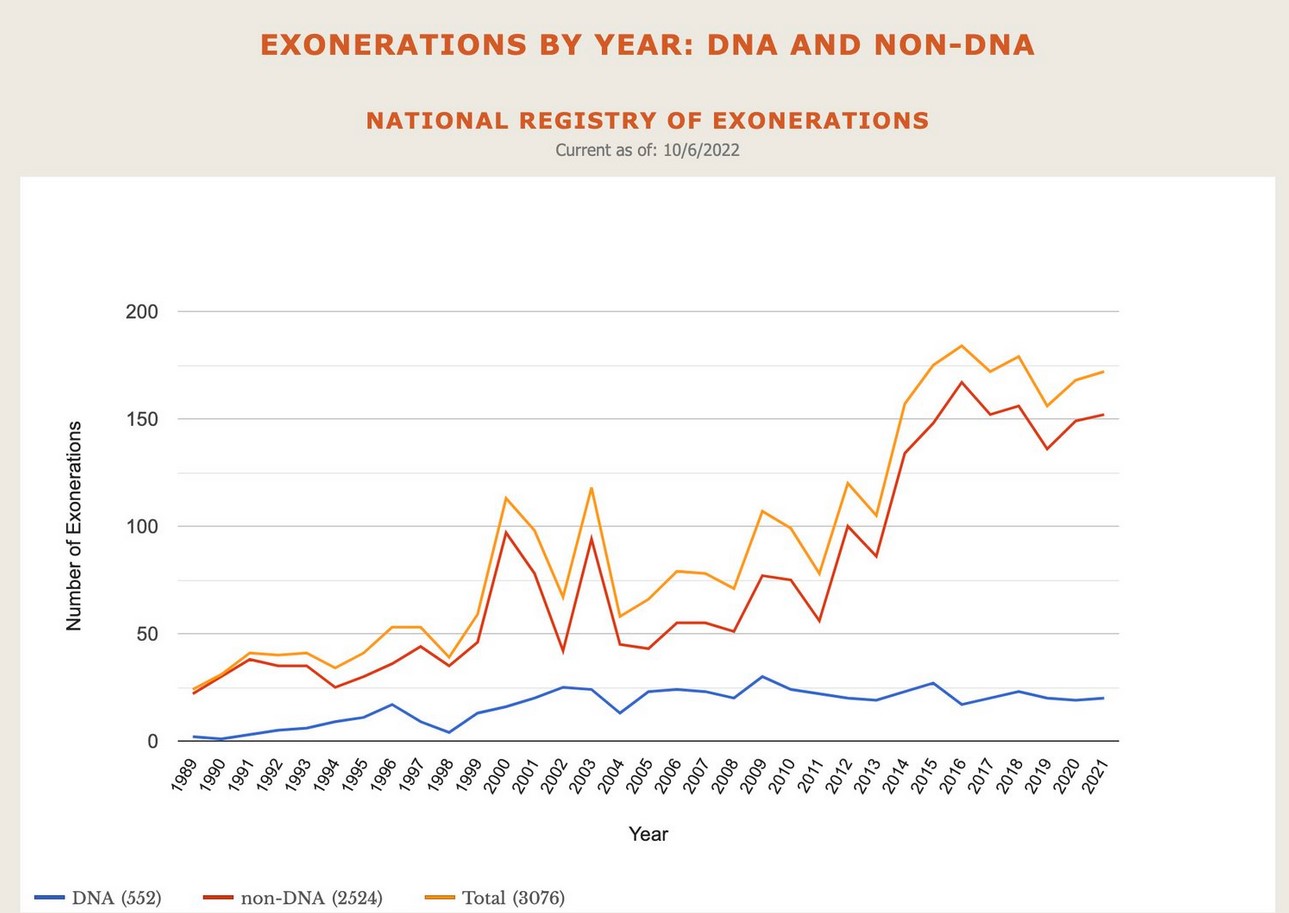

Of the 190 exonerations from death row, DNA played a central role in 29 of those cases, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Florida leads with 30 total exonerations, Illinois follows with 21, Texas with 16 and North Carolina with 11. But, over the past seven years, the number of exonerations from Mississippi’s death row has more than doubled, from three to seven.